11 October 1971

SALVATION AND A BONE RING

Today she has emerged as a Primitive painter with a growing reputation. She has also written a book, in collaboration with the psychotherapist Dr Joseph Berke, Mary Barnes: Two Accounts of a Journey Through Madness, which is one of the most moving accounts of madness ever written.

Mary lives in two attic rooms at the top of a tall house in Hampstead now but until last year she was still a resident at Kingsley Hall, a centre in the East End of London which until recently was used for the care and treatment of people with severe emotional disorders. The brainchild of Dr Ronald Laing, the psychiatrist and author, it was run more as a community where patients and staff helped each other than as an organised mental hospital.

It was at Kingsley Hall that Mary Barnes had her last great spasms of madness and where she believes she was "born" again.

'I had been in an ordinary mental hospital for a year," Mary told me recently, "and had spent most of my time in a padded cell. Several years later I met Ronny Laing who told me of his plans for Kingsley Hall He said it would be about a year before the centre was opened and that if I could sit on myself for this time I could go and Eve there.

'When I first got to Kingsley Hall I was extremely frightened and wondered what was going to happen to me After a while I began to realise that I had come there to have a nervous breakdown. I remember saying to Ronny that I needed to go back before I was born and come up again.

'I can recall when it started happening to me. I was still working as a nursing sister at the time, although I was living at the centre, and one day I was

standing in the kitchen dressing myself to go to work. I couldn't seem to get my hair up right and my stockings kept falling down. My teeth were chattering and I felt extremely cold. I rang up the hospital and said I wasn't coming in. Then I rang up Sid, a friend of Ronny's and he told me to go to bed. I stayed in my bed for more than four months.

"One night I got hold of a tin of black paint and started painting black breasts all over the walls of my room. I wanted to paint and I wanted to suck those black breasts. I was fed from a bottle most of the tune and wet my bed all the time. This gave me great relief. I was completely naked and didn't want anything on me at all. I wet myself continuously and used to smear it all over the walls."

This was the first of two radical breakdowns that Mary had at Kingsley Hall. It was Dr Joseph Berke who helped Mary to leave her bed after the first one. She was still in a babyish state and he gave her some scrap paper and told her to start scribbling. When she did so a picture emerged of a woman kneeling with a child at her breast. Finally she began painting on any surface she could find at the centre, working with a compulsive speed and energy.

It was her painting that led in a sense to her second breakdown. The other people at Kingsley Hall objected to the walls of the building being covered with them. This drew her anger and precipitated her crisis. She retired to her room again and this time stayed there for more than a year.

During this breakdown Mary underwent her second journey back through her mind and body into infancy again. At one time she even refused her bottle and demanded to be fed from a tube. She now recognises that this was a desire for attachment to the umbilical cord and that she had, in her own mind, gone right back into the womb again. In her book her recollection of this period is woven thickly of physical detail and general sensation.

"I kept sucking on a bottle," she writes. "I bit hard on the bone ring someone got me. It had a bell on so. I know when someone held it for me to bite. It helped me. Sometimes my limbs, seemed heavy and sticky, it seemed I was a little animal, gone to sleep for the winter. My body did often seem apart. A leg or an arm could be the other side of the room. Often it seemed I was floating and moving as if in fluid."

Mary now believes that she achieved her desire to be born again towards the end of this bout of madness. "What had happened was that I had rejected my life completely," she explained, "and I needed to start again to find my true identity. During the Christmas of 1966 I remember Ronny came to see me in my room. I was talking about the Mother of God and he mentioned the Resurrection. In a few days the thing seemed to have sort of broken and I started coming up again.

"Of course it didn't happen all at once. Only very slowly was I able to bring my feelings up into my thoughts and my thoughts, as it were, down into my feelings. I was growing up again you see, oven though I was a middle-aged woman, and learning my true nature. In fact it has been only in the last year that I have finally begun to feel more together with myself and have been able to come to terms with my real age.

"Sometimes I realise quite how much I have changed emotionally. This is very important to me. It is because I am different way down underneath, and that I have at hut started to find myself, that I am able to enjoy my life in a way that just wasn't possible before."

The lease on Kingsley Hall ran out last year and the staff and patients had to leave. There are plans now to establish a similar centre as soon as possible, when premises and the necessary finance can be found. Mary was lucky enough to find two attic rooms in a Hampstead house, where she now lives simply and frugally on advance payments on her book.

The only things she had brought with her were her bedding, a cushion she had made at Kingsley Hall and two dolls, which Joseph Berke had bought her during her "second" childhood. She has since acquired a lampshade of hanging twigs, together with a stone crucifix she made herself, and a copy of Where the Wild Things are, a brilliantly perceptive children's book by Maurice Sendak.

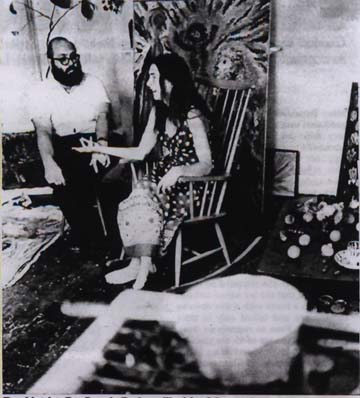

Psychiatrist Dr Joseph Berke still visits Mary twice; is sometimes nothing more than a desperate bid for liberty," he says.

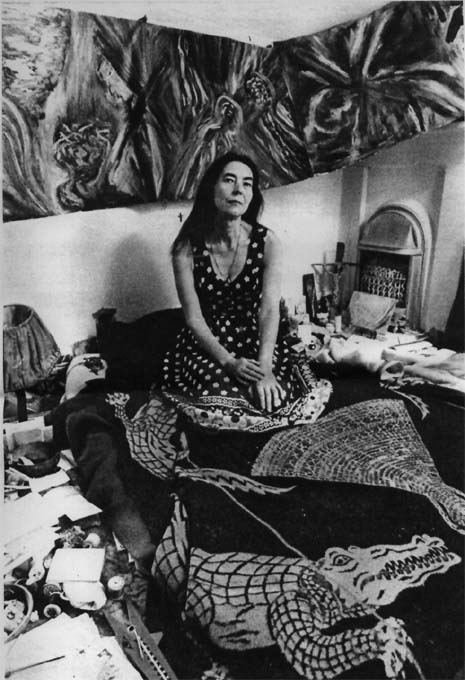

When I met her she was sitting among this tiny litter of possessions like

sonic mystic female ascetic. She wanted to be a nun once and, with her long dark hair and flowing clothes, she

seems like the priestess of some sect whose secrets can only be penetrated through personal suffering.

The roots of madness are dark and complex. With Mary they seem to be indeed in the womb. Her mother was the kind

of strict but loyal woman to whom life, and certainly sex, was a penance. She was in labour for three whole days

before Mary was finally born. The emotional landmine in Mary's memory during her madness was this recollection

of a difficult and reluctant birth.

Family life was more a matter of duty than natural affection. There was little encouragement of love and feelings.

In Mary's book this overwhelming sense of emotional repression is expressed in a series of pained and vivid metaphors.

"Life was like brittle ice," she writes. "The whole family wanted this ice to melt, wanted to be

loved. But we feared if the ice broke we would all be drowned. Violence and anger lurked beneath the pleasantries.

On the surface we were a kind family. Physically we were well cared for, good food, lots of milk, fruit and eggs,

clean clothes and a big enough house. Deep down we were tom up with hatred and strife, destroying, killing each

other. Our love was sour."

It was this emotional repression, and the fact that she had no freedom to develop her own nature, that Mary feels

today caused the intense and cumulative anger become madness.

When Mary grew up she become a nurse. Today she realises that it was not what she wanted to do at all but had imposed

the profession on herself out of a sense of guild. It was during a stay in a convent that the first signs of madness

appeared. What happened was that I started to get stuck in my body," she told me. I couldn't talk to anyone.

I would start playing in the garden with the dirt. In fact I was starting to become a child again.

Mary was lucky to be admitted to Kingsley Hall. Had she stayed in conventional mental hospital she might well still

be in her padded cell. At Kingsley Hall she was allowed to "act" out her madness in a way that led finally

to her salvation. As Dr Joseph Berke says "madness is often the result of struggle to disengage from a role

imposed by other people. It is sometimes nothing more than a desperate bid for liberty.

It is not true been "returned" intact to the conventionalised real world, She has no desire to adopt

a "normal" life within a community. When the proposed new Kingsley Hall is established she hopes to join

it again.

'I hope that just by living in such a community I will continue to grow and develop," she says, "and

by living this way be able to help others."

Meanwhile she will tell you simply that what happened through severe madness was that she was "born Again".